Mega Robo Exit Interview

Everything you ever wanted to know about Alex and Freddy, and then possibly some more too

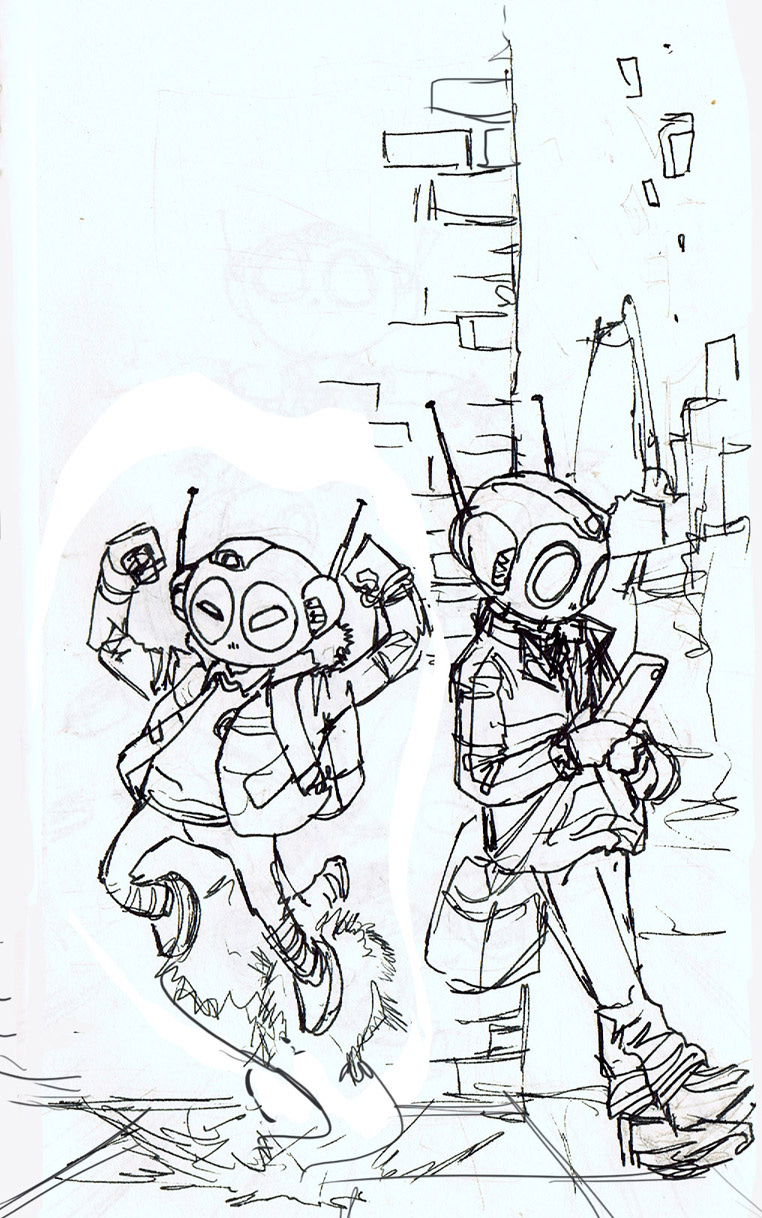

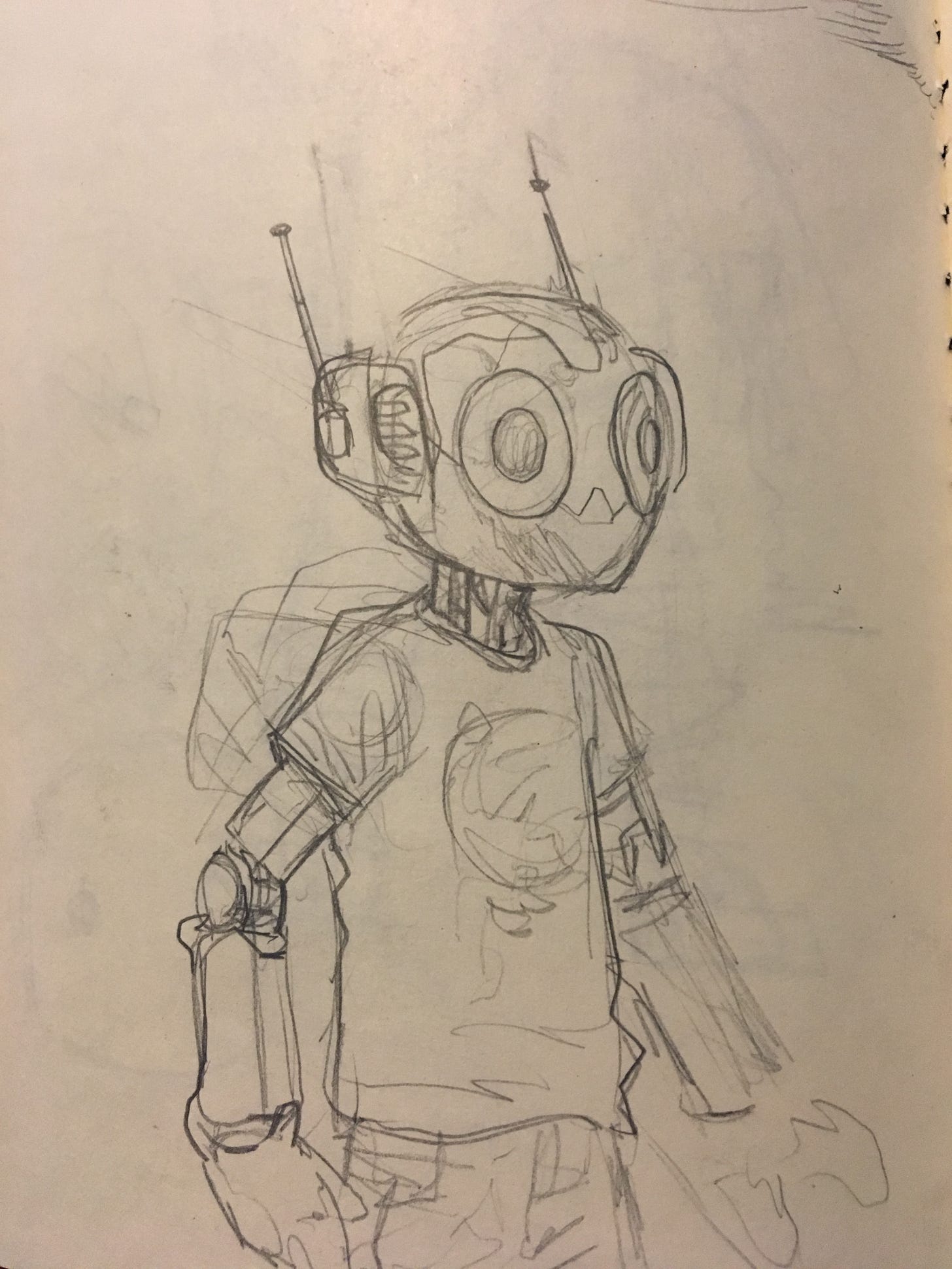

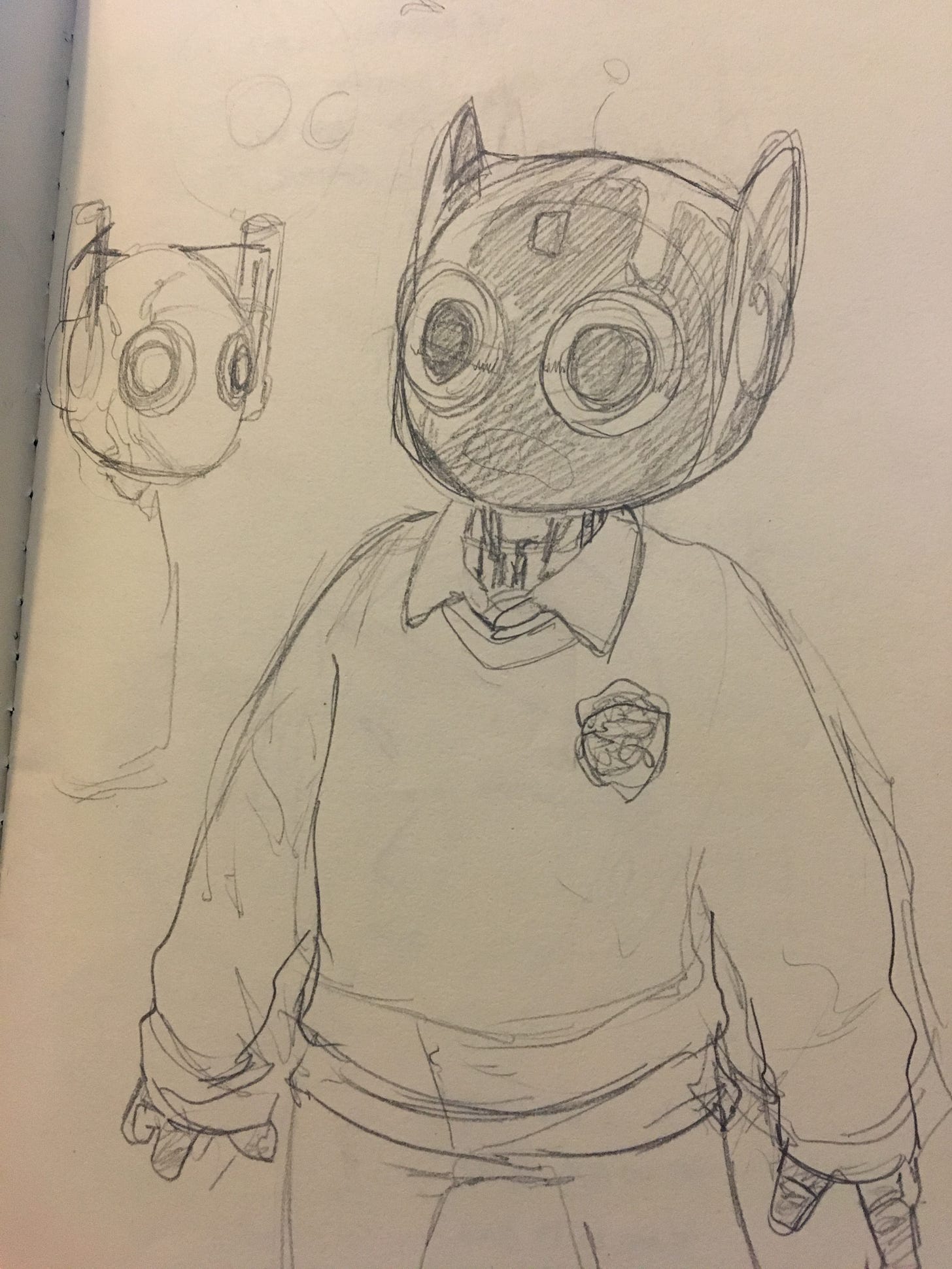

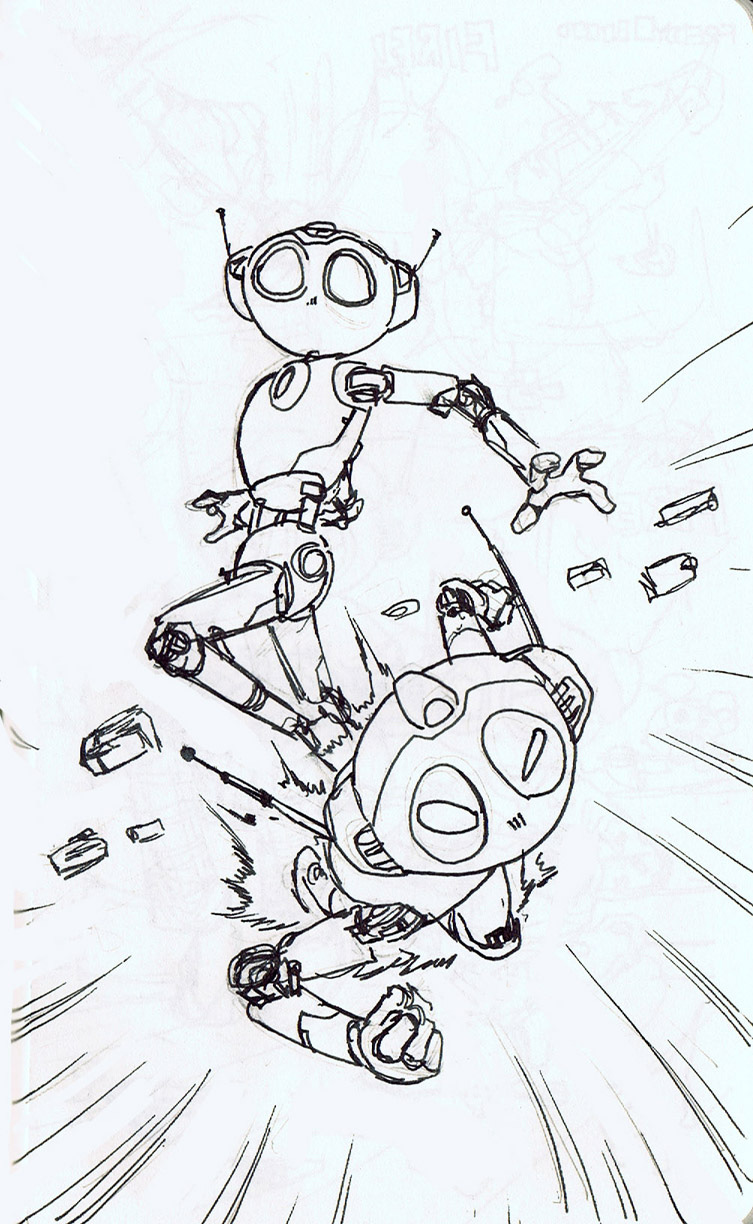

As I mentioned the other day, a while back I had a long chat with my friend Matt Finch about the end of Mega Robo Bros, and the beginnings of Mega Robo Bros, and everything in between. We spoke back in January, just as the story had come to the conclusion of its ten-year run in the Phoenix, and it was wonderful to have the opportunity to debrief and reflect on the whole thing with Matt who, as I may have mentioned, is rather marvelous. We agreed to hold off on posting the interview until the final book was out and people had had a chance to read the conclusion. And, I think, by now you have - although please RUN DON’T WALK TO BUY A COPY OF MEGA ROBO BROS FINAL FORM if not - so here we go. This already appeared on Matt’s blog but I thought it’d be fun to post it here too, with relevant accompanying illustrations and bits of roughs and concept art and stuff. Please consider this the back matter at the end of the final book, if we had remotely had page space for such things.

I will merely note that (1) this is a proper Long Read, and (2) it contains discussion of plot points literally all the way through MRB, right up the other ending. So make yourself a cup of tea, brace yourself for spoilers…

Okay. Ready? Here we go…

Mega Robo Bros: The End

Neill Cameron interviewed by Matt Finch, 10th January 2025

Matt:

So, here we are at the end of Mega Robo Bros…when was the moment this series ended? Was it the last pen stroke on the last frame? Was it when you figured out the last story beat? When did you feel, “Okay, this story is done?”

Neill:

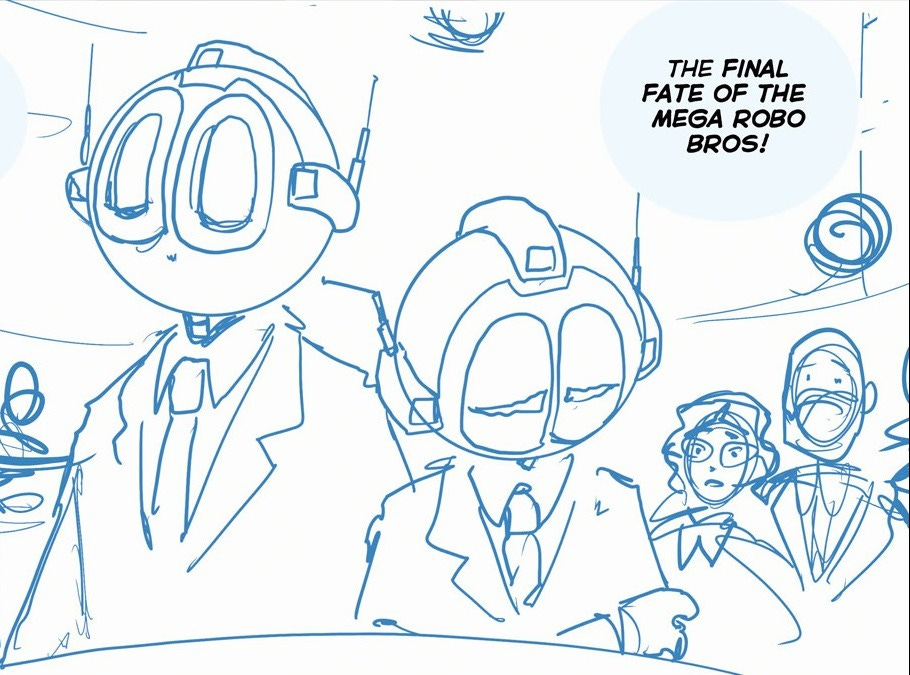

In a way, it sort of hasn't finished for me yet, because people who read it in The Phoenix have come to the end and been through the whole experience, but we also have separate readerships by this point. There are people who have grown out of their Phoenix reading years maybe, or never came across the Phoenix but read the series in book form. And they're still waiting to find out what happens after Freddy turned evil at the end of book seven! They're still hanging on out there; this must be a very annoying and frustrating time for them. But while it's still active in that way, I get to pretend it's still going on to some extent.

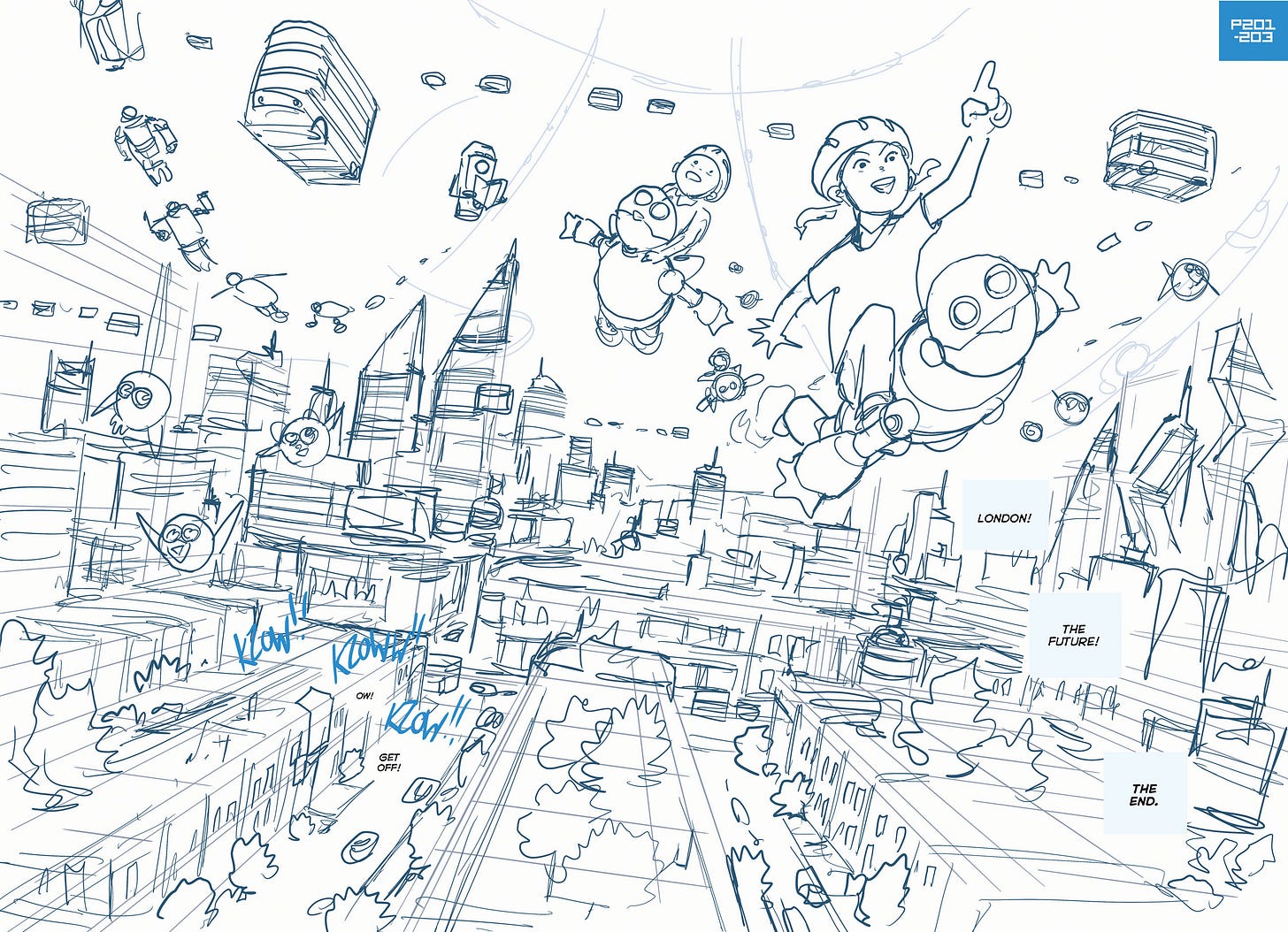

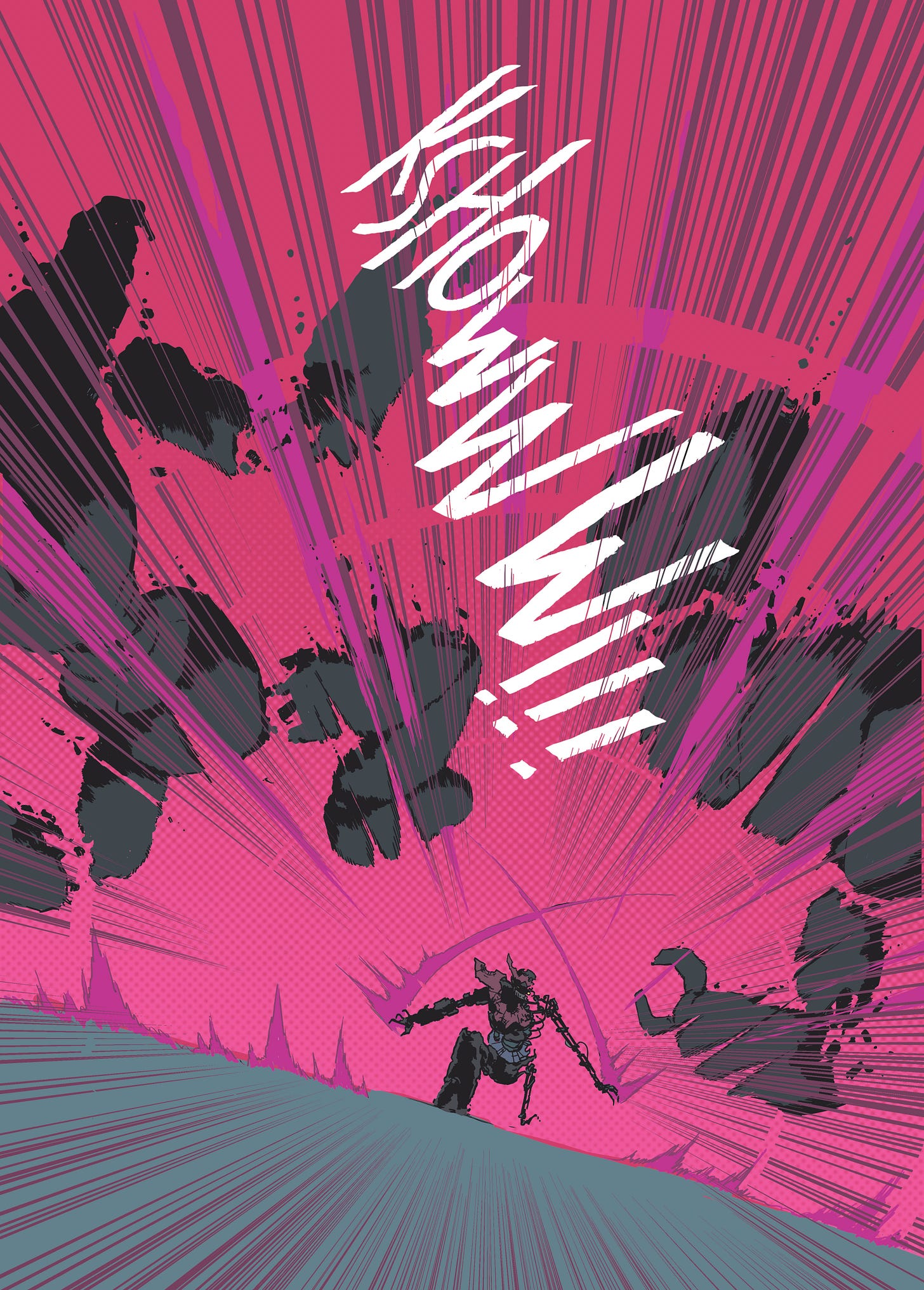

In fact, MRB has ended many times for me. The first one was writing the outline for the last story; figuring out the ending in any shape or form. Then you come to draw it, doing the roughs and going through the various versions, then drawing the actual pages – that was probably the most significant one. Then you really do feel, “I’m drawing all these characters for the last time, drawing scenes and moments I’ve been thinking about for ten years.” And you feel that you only get to do this once, so it’s a big moment, but then you’re going through the inking and the colouring, and then it’s still coming out every week in The Phoenix. So it’s ended about twenty times already, and it’s probably gonna end about three more times!

Matt:

Robot 23; 23 endings.

Neill:

Seems about right.

Matt:

So does that mean you've had this sense of, not mourning exactly, but saying farewell, twenty times with another three to go? How hard has it been saying goodbye?

Neill:

It sounds a bit silly, but it has been hard. Certainly going through and drawing it all, there were times when I was finding it a bit emotionally overwhelming.

I mean, yes, you’re saying goodbye to fictional people who do not really exist, and I'm aware of that, but making comics is in some ways a really intense form of writing – the way I do it, anyway - because it takes so long. You go through each step of any scene, any story, any volume, multiple times – writing, roughing, pencilling, inking, lettering, colouring - and so you’re living with it and still thinking about the story through each of those stages.

One of the great aspects of this is that, at least in theory, what ends up on the page has been really carefully considered and it’s exactly what you wanted it to be after having all this time to live with it and think about it. But that intensity also means that when you get to those big emotional moments, you hit yourself pretty hard with them, you know? And you’ve had something take up that much room in your head, that much emotional space, and then it goes away. I’ve been thinking about this for ten years and, well: what do I think about now?

Matt:

That space of uncertainty that now lies ahead.

Neill:

Yeah. Yeah.

Matt:

We’ve spoken before about how the decade-long run of MRB parallels your son’s journey towards finishing high school. In a way, when you have a kid of that age, you know at 16 or 18 there’s going to be a transition. That element of the future is kind of certain. In the same way, how much did you know the exit point for the Bros when you embarked on this? How much of the story, including the ending, was pre-written or half written in the back of your mind?

Neill:

Quite a lot really, because there's key moments in the ending, key scenes and revelations, that were always there. They were the initial idea, my initial “Oh, you know, what'd be cool? A story where this happens.”

Matt:

What were the bits of the ending you could already see from the outset?

Neill:

In the last volume you finally get a flashback to where the boys come from, and their mum meeting them for the first time; Alex standing there holding little baby Freddy in the middle of this giant smoking crater. That was basically the seed of the entire story, that scene, that moment. That’s where it all came from, and that, coupled with the shocking revelation of who the baddie actually was the whole time – which was the other big bit that I knew – those were the things I knew we were building towards.

There’s a third element, but this changed a lot as we went through it… My thought was, you wouldn’t want to have the entire story locked in place before you started and then just draw it for ten years. That would be stultifying. Still, I knew that ultimately this was in some way a coming of age story. You had a child going through school and getting to the end and graduating. At some point, the ending was going to be Alex growing up. The specific form that took, however, was the part that kept it interesting for ten years, because it took forms which I might not have originally expected. And what that meant was that the ending was also something we found along the way.

Matt:

Makes sense. Is that how it feels for you, as a writer? There are always people who identify as plotters who organize the whole story structure in advance, and others who write by the seat of their pants, and all kinds of odd ways of categorizing or self-categorizing. What’s the process like for you?

Neill:

With comics, and particularly a weekly comic telling a story episodically with specific page counts and so on, it forces you to be quite a plotter. It fits me quite well, in that I like to have that basic structure and to have the shape of the thing in place quite early on. But it’s through actually getting into it and telling the story that you find a lot of the actual joy of the story and the character, the emotion; the stuff that actually makes it come alive is the stuff you find along the way. So as long as you don’t have such a rigid architecture in place from the beginning that you deny yourself any room for all the joyous discoveries along the way, then there’s a lot of fun to be had in that tension.

Matt:

Do you remember any specific moments of joyous discovery? Were there times when the story or its characters surprised you over the tenure?

Neill:

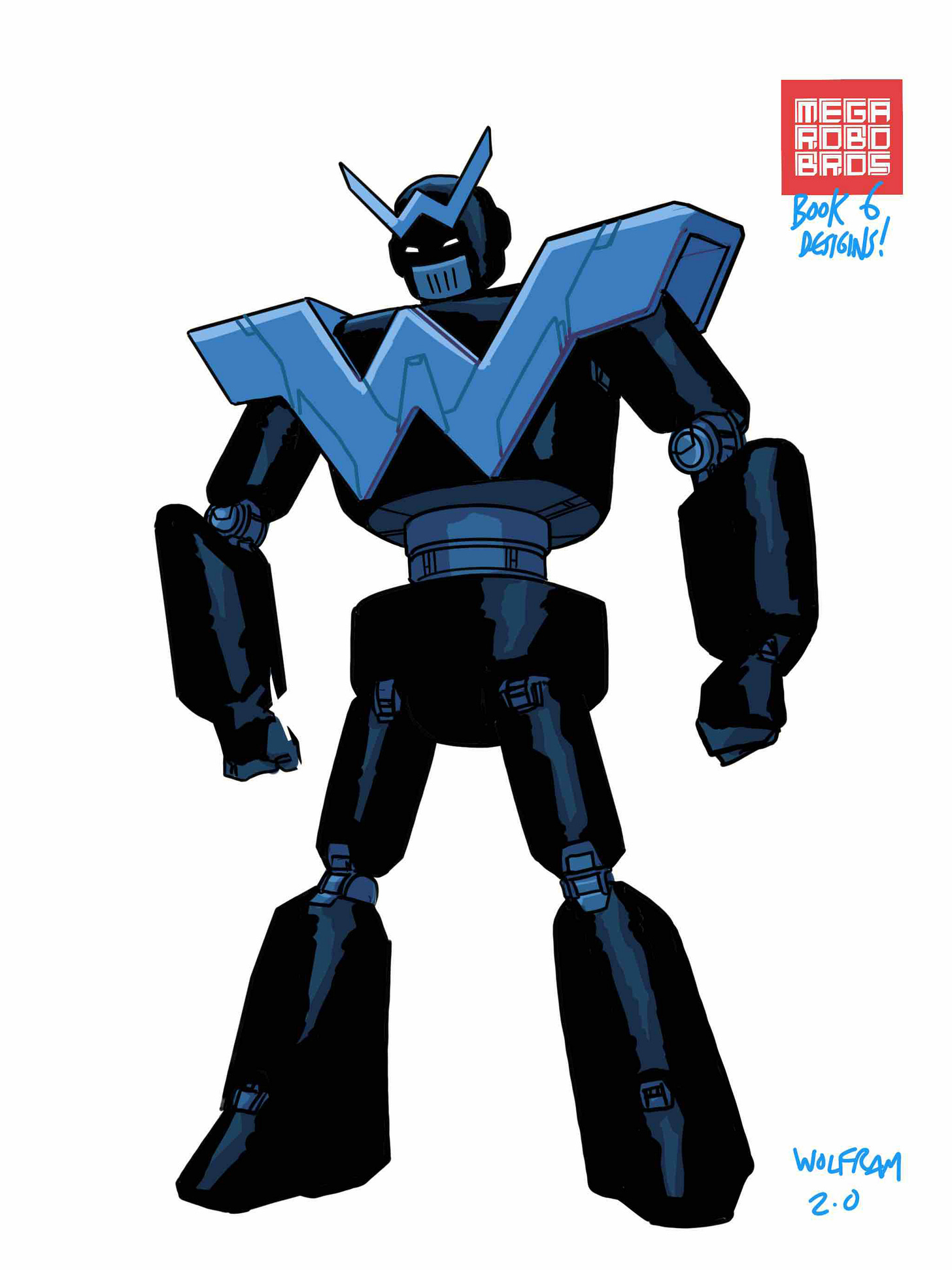

There’s so much that wasn’t in the plan. The character of Wolfram wasn’t really there, for example, and he ends up being one of the biggest characters in the story – the poor, poor guy! That was pointed out to me towards the end by one of my editors, Joe Brady. He was writing the catch up pages in The Phoenix, and he really went to town on them. Towards the end, he got a full page because there was so much story to catch people up on.

Each issue of The Phoenix is someone’s first. So Joe was summarizing ten years’ worth of story each week, and he’d theme them. So, during a big Freddy episode, you’d get the whole thing from his point of view, or at the point of the Robot 23 reveal, you got the entire story from his perspective. And when Wolfram had his heroic moment and saved Alex, freeing him, finding the brotherhood he’d been searching for all along, you got Wolfram’s life story in the catch-up page, with all the horrible things he’d been through. And that was when I realized what a big character Wolfram was, when Joe put that page together, and said, “You’re a monster, Neill! No-one has suffered as much as this guy!” It wasn’t my intention at the start, but it was one of those things I found along the way.

Matt:

Eighties Transformers comic energy.

Neill:

There's no way it couldn't have had that energy

Matt:

Yeah. I feel like there's some of that in your DNA, never mind your comics! But I wonder if we stay for a second with that question of suffering, I think one of the most deft things in this book is it is set in a always sunny future version of London that is suitable for a kid's comic. And yet by volume four, you have the destruction of Perth --

Neill:

Yeah, sorry, Perth!

Matt:

-- and you have Wolfram, and much more besides. There is an awful lot of suffering, including the fact that our oldest protagonist is culpable in taking someone's life, albeit for good reasons. By the end of the series, we've come to a degree of moral maturity, facing up to ambivalence and ambiguity. It's a big stretch from where we start in volume one.

I wonder if you could talk about what it means as a responsible kids’ writer to go through this journey: “You're going to come and read this comic every week, and it's safe and it's fun, but we are going go to some of the absolute darkest places.” How did you handle that journey?

Neill:

First of all, with very close, careful, skillful editing. I’m very fortunate to work with some of the best, most sensitive, thoughtful editors I could possibly have, who know the Phoenix readership so well, and come from a children’s publishing background; they’re not scared of putting kids through it!

I never had the sense, “Hey, back off, don’t do this”. When we do have difficult conversations, it’s usually about whether it’s reasonable to expect parents to have a conversation with their children about what they’ve read in the comic. Our readers might be six or seven years old, it’s not necessarily your job to introduce them to certain concepts or experiences, so we take great care in thinking about where we’re taking them. And we try to ensure that even if we are going to some difficult or new places, we do so in a way that means the wider world around them does always feel safe and welcoming.

Matt:

The style of your artwork and the colours do some of that work too.

Neill:

For all that unpleasant things happen, and there’s danger out there, and characters are in jeopardy, the overall tone of the MRB world is one where you are always surrounded by family and friends who unquestioningly have your back and love you, accept you, support you. So the emotional framework is very safe. In a way it’s the opposite of classic children’s fiction, where you might kill off the parents on page one so that the child has to go through danger and can’t just call on adults for help.

I think that so much of Alex and Freddy’s story relies on the parents, friends, and family around them. That doesn’t mean there’s no danger or trauma, but it’s about looking at what you still have to face and figure out and deal with, even with a loving support network around you.

And again, I guess I’m drawing on the 1980s Transformers playbook here, but a lesson I learned at an early age at the feet of Simon Furman is: you can get away with a surprising amount if the characters are robots! You can put them through it emotionally, but you can also dismember them, have levels of violence that would be just wildly unacceptable in a children’s comic if these were human characters. All those goodies and baddies just getting torn apart! If they’re robots, you can do that stuff and go to places with the Mega Robo Bros that you couldn’t if they were human children.

Matt:

There's something about the way we relate to machines at this particular point in human history that is really interesting in terms of what this comic does. Here we are, on the cusp potentially of the rise of talking, thinking machines, and we have the Mega Robo Bros arrive to help us think through these issues.

The comic also has the quality of a fairytale, including that darkness; you have good stepparents, a wicked birth parent, and you know, Alex ends in this wonderful position where – if there were ever an Alex and Eustace spinoff! – Alex has the opportunity to be a non-binary princess.

There’s a kind of thread of fairytale in this work, not in the sense of “recapitulating a classic myth, but with robots”, but rather tapping into something deeper yet totally contemporary. What part do fairytales and traditional storytelling play in your work?

Neill:

It’s all right there on the page! I freely take those elements and just try to use them in a way that relates to the modern world, rather than a reheated version of a cautionary fable for children in the middle ages!

Matt:

I love the idea of MRB as a reverse cautionary fable. It’s almost an invitation to take flight, rather than retreat from the darkness.

Neill:

I like that. I’m having that!

Matt:

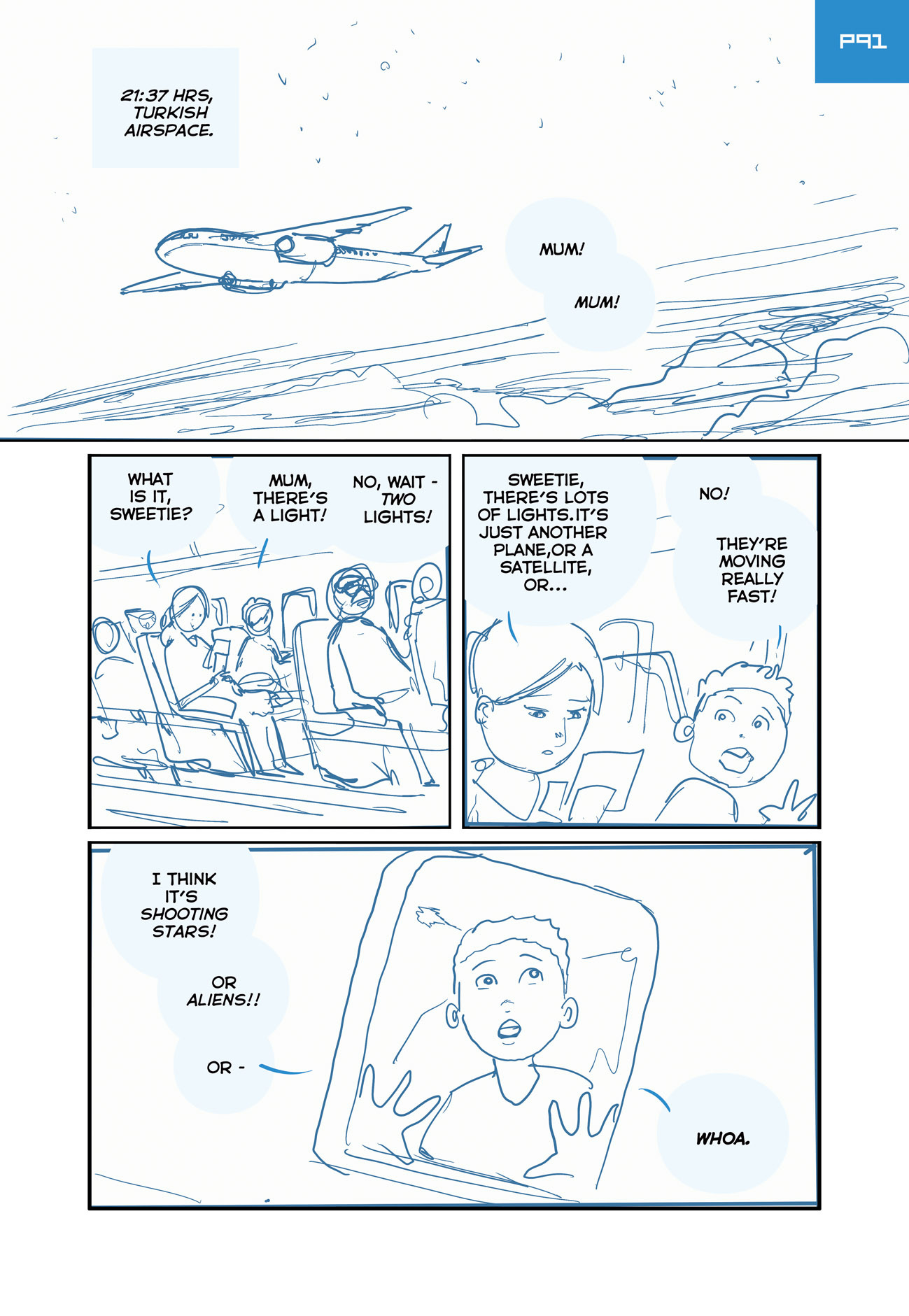

A moment in that vein which stands out to me…You don’t waste a frame, you don’t waste a page, you’re mindful of the book’s episodic nature and you don’t succumb to exposition, yet you keep this one magical moment which is not a story beat, where the Bros are in flight and a little boy sees them through the window of a passing jetliner. And he’s like, “That’s cool.”

Neill:

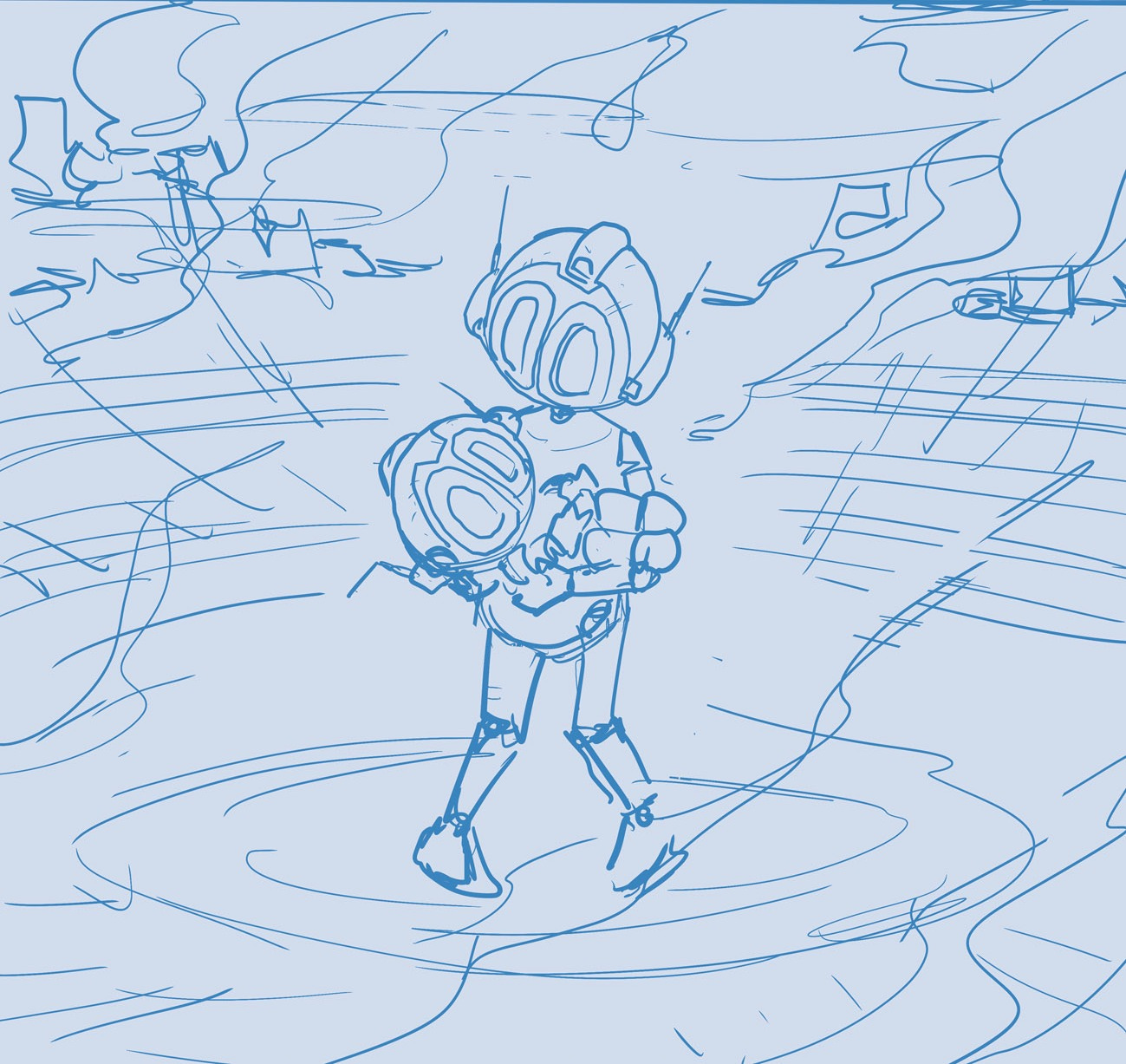

Yeah, so they’re flying to Azerbaijan at supersonic speed, and they pass by this commercial airliner. And I just felt at a gut level, they just recently got their powers back. They can fly again now! And we’re just coasting on that emotional high. And at that point in the story they’ve been so caught up in their own concerns, their own history, backstory, personal struggles, I wanted to connect them back to the wider world.

And that moment did maybe feel slightly indulgent, and I am mindful of how ruthless page count can be – so many precious, beloved moments get cut! – yet this one felt important at a level that wasn’t even conscious. You just know this moment needs to happen at this point. It’s Raymond Briggs’ Snowman and the kid in the dressing gown flying past the windows of that little Germanic village and the child in the window looking out to see them in flight. It connects things back to the reader, via the kid, and just allowing that moment: “Wow, that’s cool”.

Even when it’s all very intense and dark, you’ve got to have the moments when you just look to the sky and marvel.

Matt:

I think it’s really significant that this comic understands its magical moments are wistful ones as well as the outrageously cool bits or the moments when something goes bang. And perhaps the most magical part of the journey is the sensitive, nuanced, and very open-ended exploration of identity that Alex goes on. Was that there from the outset? How did you go about ensuring that unfolded in a way that really worked for your readers? Can you also talk a little bit about what it meant as an author to, to create Alex's journey - or accompany Alex on that journey?

Neill:

That whole aspect of the story was there, if not from the first moment of conception, then from the second. The eight volumes of MRB are my most eloquent attempt to talk about this stuff.

This was also one of the key areas where my editors would maybe tell me to tread more carefully, or go a bit more slowly, or make sure things worked on a sort of metaphorical level, as well as just on a quite literal level.

In the first series, there was an episode with Alex having a conversation with his dad by the canal early on which got a bit emotional. It said some of this stuff up front and explicitly, a lot more clearly – there’s no scene like that in book one now. It was one of the few places where it was suggested “You need to pull back a bit here”. I was maybe a bit grumpy about it at the time, but again all respect to my editors who, I will grudgingly concede, possibly do in fact know what they’re doing.

Eventually it became a constant thread through the story – not a question that is answered for a very long time, until perhaps the very end. And that is the ending in a way. That tension and ambiguity of a kid trying to figure this stuff out? That is the story of Mega Robo Bros. It might have been disingenuous for Alex to arrive at any kind of definitive answer early on, because the process of trying to figure things out really is the journey.

Part of the work was really thinking through Alex’s journey, that this wasn’t just a metaphor specifically about trans or non-binary experiences; this was important because I’m not trying to represent anyone’s specific experience, and I had wrestled with the question, “Do I have the right to tell this story? Am I trying to lay claim to experiences that are not my own?” I didn’t want to tell stories that I wasn’t entitled to. In the end, after ten years questioning myself and worrying a lot about this kind of thing, I find I’m not really telling anyone’s story but my own, and I feel okay about my right to tell that story.

Matt:

You talk about questioning yourself quite harshly. You talk about the difficulty of the work and the grumpiness one feels one runs up against constraints. You know, there's this old joke, no one enjoys writing, everyone enjoys having written.

And I can see the delight you get from the story living on with an audience and from your interactions with readers. But do you enjoy this work? Or are you called to it despite the fact it's not always a fun gig? What's your relationship to writing? Is it something you want to do, have to do?

Neill:

I can make it sound very much like I’m the tortured artist; there’s no denying it’s hard work! And I never wanted to be a writer, it was more that I wanted to draw comics and at some point ran out of comics to draw, so needed to make up my own. So it all slightly happened by accident!

I’ve come to accept, eventually, that I might possibly be a writer… I mean I’ve written like a whole shelf of books, I can’t really dodge that at this point! But I do find it very difficult sometimes, much as I love telling stories. I love drawing comics more than anything, but the coming up with stories in the first place? Getting them to a point where you’re happy with them? There’s a lot of pain to that, it can be an ordeal!

At the same time, there’s no better thing in the world. I have good days and bad; I don’t want it to sound too gruelling and traumatic, and I am highly aware that some people have real jobs. But it can be very demoralizing when it’s not working…though when it clicks and it is working, it’s the best feeling there is.

Matt:

If you imagine someone reading this interview, maybe someone who grew up with the Bros and is trying to see if they could write and make comics, I think hearing this from you is good: that there are elements of doubt, that it is hard, that it is real work even if it’s not a nine to five.

Neill:

I do worry that I spend a lot of time encouraging kids to draw and write, to make their own comics, telling them it’s fun and easy and great and rewarding. And it is all of those things! But I could also be setting them up for a life of creative hardship and self-loathing and challenge.

Matt:

I think of that book of emails that Russell T. Davies did about writing Doctor Who. And afterwards, the other Who showrunner Steven Moffatt said, if someone reads this and still wants to be a writer, they'll be a writer.

Neill:

That is one of my favourite books about writing. He’s just so brutally honest in those emails about the horror of it, the bit before it clicks and comes out. Imagine being him and still feeling that way! He writes so much, how does he have time to sit around feeling all that sickness and doubt and uncertainty that it’ll never work! It’s crazy, isn’t it?

Matt:

In your own way, you are also one of those kind of figures. You go to book fairs and festivals and schools, and there’s a level of celebrity for kids who read the Phoenix, who read your books. How do you deal with the responsibility of being that kind of public figure? And when, in turn, have you felt that starstruck sensation? I wondered if you could talk about that in both directions, being the fan and being the object of fandom.

Neill:

I mean, it is weird. I was just in Ireland at the weekend for a little children’s comics festival in County Wicklow. It was absolutely lovely and I was pleasantly surprised to discover that anyone had heard of me at all. And some people were quite excited for me to be there. But I was saying to one of the other authors, there was this one moment where a kid came along to get some books signed, and the people who were running the festival told me that he'd come in to the local bookstore and found out that I was visiting. And it had completely blown his mind because he had somehow discovered these books in the library, and no one else he knew had ever heard of them.

He'd gone to amazing lengths to track down the other volumes. And then he discovered that I was going to be there, in his little town. So there was this one kid who was really invested in my visit. That’s the nice thing about my level of relative obscurity: something like that can happen, and it just feels like magic. For me in my childhood, it would’ve been something like Simon Furman coming to our school.

So on these visits you just try not to disappoint and not to be a jerk. I work with kids a lot, and I just try and talk to people of all ages as human beings and individuals. I also try to be sensitive to the fact that some kids will just completely clam up in your presence. I’ve told children a couple of times at signings about my experience when Terrance Dicks, the Doctor Who writer, came to a bookstore in Oxford. I took along my novelization of The Five Doctors to get signed. I still have it somewhere! I was excited for weeks, couldn’t sleep: Terrance Dicks! Just imagine.

And then I get there and he’s an actual human, middle-aged, man – and I have no idea how to talk to him. I just sort of stand there frozen in panic, and get my book signed, and walk off without probably saying a single word, you know! And I get it. Talking to grownups you don’t know is quite weird for some kids – let alone with the emotional pressure you might feel if you’re a fan of their work. So I just try to be as nice as I can so that they hopefully have a nice memory to take away other than just, “I froze! I couldn’t say anything!”

Matt:

I imagine it’s also about balancing the solitude of your creative work with the performance aspect of schools visits and the like. What’s that dance like for you, going between being alone in a study to the focal point of attention at an event?

Neill:

I know for some writers and artists, it’s really hard; turns out for me, going back and forth between those two modes is enormously psychologically helpful. It keeps me balanced, on an even keel. I think if I were just sat in my room drawing, and that were my default mode and only safe place, that might not be great. And it has been very good for me to learn that I’m actually a bit of an attention queen. I just love having a whole room with people all listening to me talk – I love making a room full of people laugh.

I can totally see why standup comedians and the like get hooked on it. Saying something you consider funny and having a whole room full of people laughing is one of the greatest feelings I think it’s possible to experience in life. I’m naturally quite an introvert, though, so after doing that kind of stuff, I’ll be totally wiped out and will need to sit and draw robots in my studio for a while. It’s just nice to discover that maybe I’m not just that quiet studio lurker that I always thought I was back when I was younger. I was a bit scared of the world back when I had to talk to rooms full of people for the first time, it was the most terrifying thing that I could contemplate. And to this day, I’ll have anxiety beforehand, even after doing it so many times at this point, but I just have to accept that, ridiculous as it is, we can’t help how our brains work. I have to trust the process and tell myself, “It’s going to be scary, you’re probably not going to sleep very well the night before, but you’re going to absolutely love it and afterwards will be completely just buzzing and fired up in a way that is hard to achieve by sitting in a room on your own!

Matt:

And just thinking about the swing between the more introspective solitary side which we perhaps see in Alex, and the more exuberant attention craving side in Freddy, there is one thing that I, and many others, really need to know:

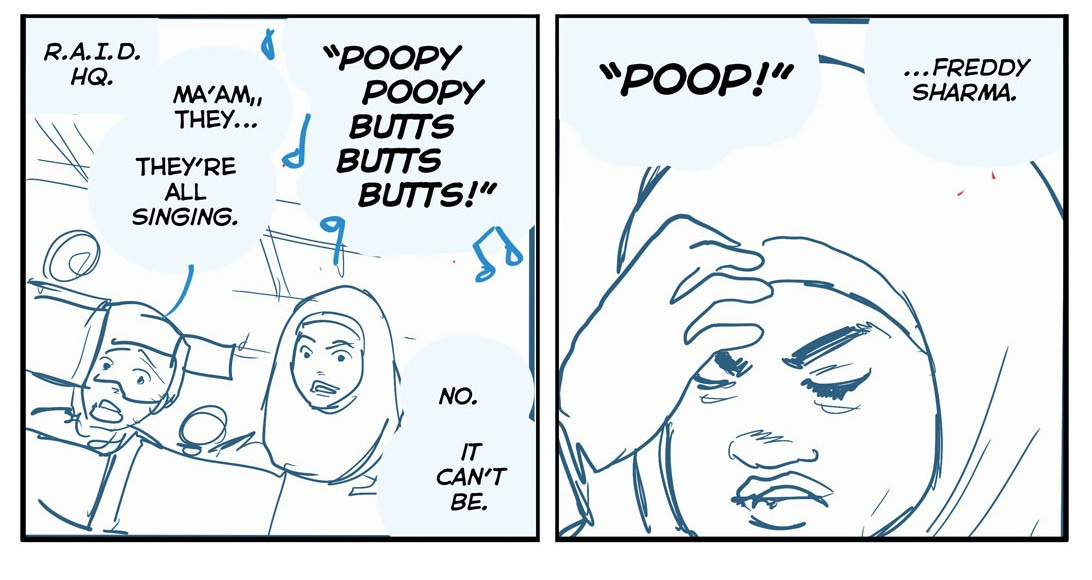

How, when, and where did the Poopy Butt song come to you?

Neill:

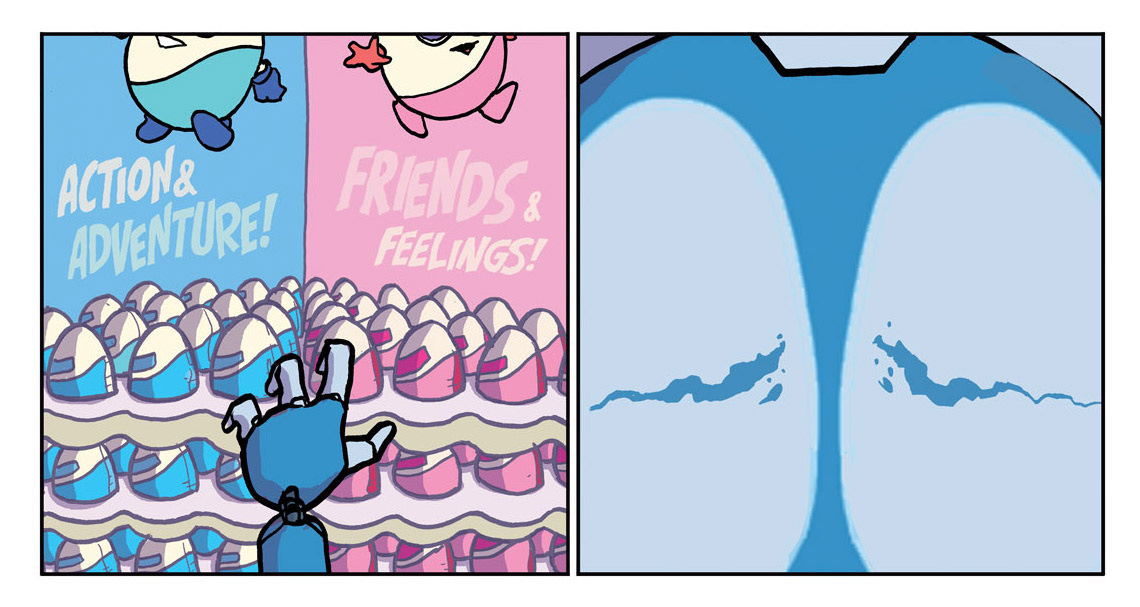

I mean, that, that's a joyous discovery along the way, right? That certainly wasn't in my pitch for the series, but it's right there in like episode two or something. It is very early on and there's a line: “Do you have any idea of the sophistication it would take for an artificial intelligence to just write a song?” That was sort of science fiction when I wrote it, and now it's just commonplace, right? I'm sure AI are writing thousands of poopy butt songs every day!

Matt:

It’s literally a song that saves the world, it is a song that becomes the gateway into self-awareness for every robot on the planet. That feels peak Neil Cameron somehow.

Neill:

I felt very pleased with myself when I saw what I could do there. I could pretend it was a perfect long set up and payoff, but actually it was exactly one of those joyous discovery moments: “You know what would be fun? If the moment when every robot achieves sentience was…”

The reality is you’re laying down stuff as you go and may you not necessarily have a plan for it, but the more cool stuff you give yourself to play with, the more chance you can then pick it up later.

It sort of sums up what’s happening all over the world, that the robots are becoming children, in a way; they’re becoming people in the way that children do – going from being almost straightforward biological machines to people…and laughing about poop is a key part of that!

Matt:

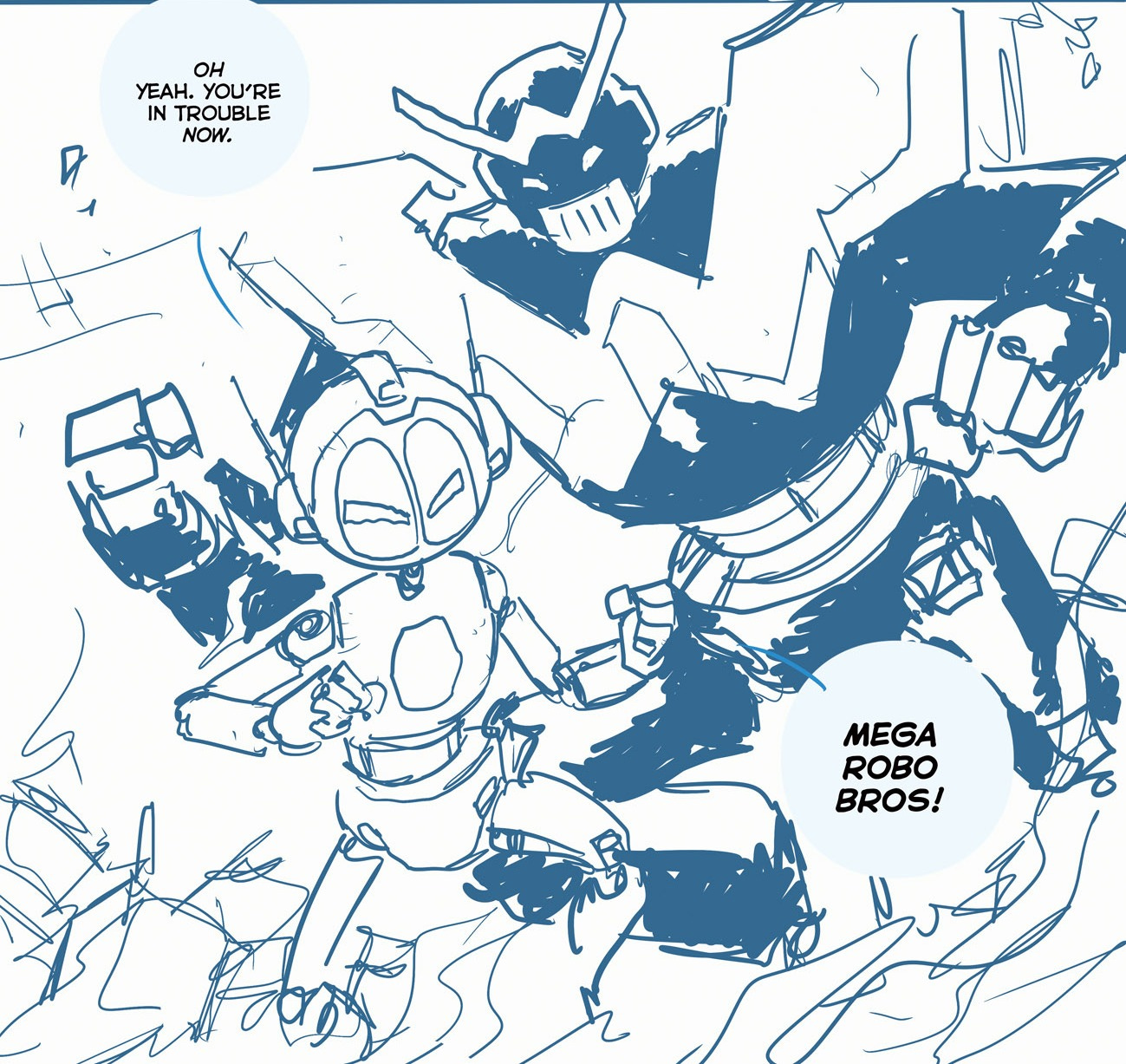

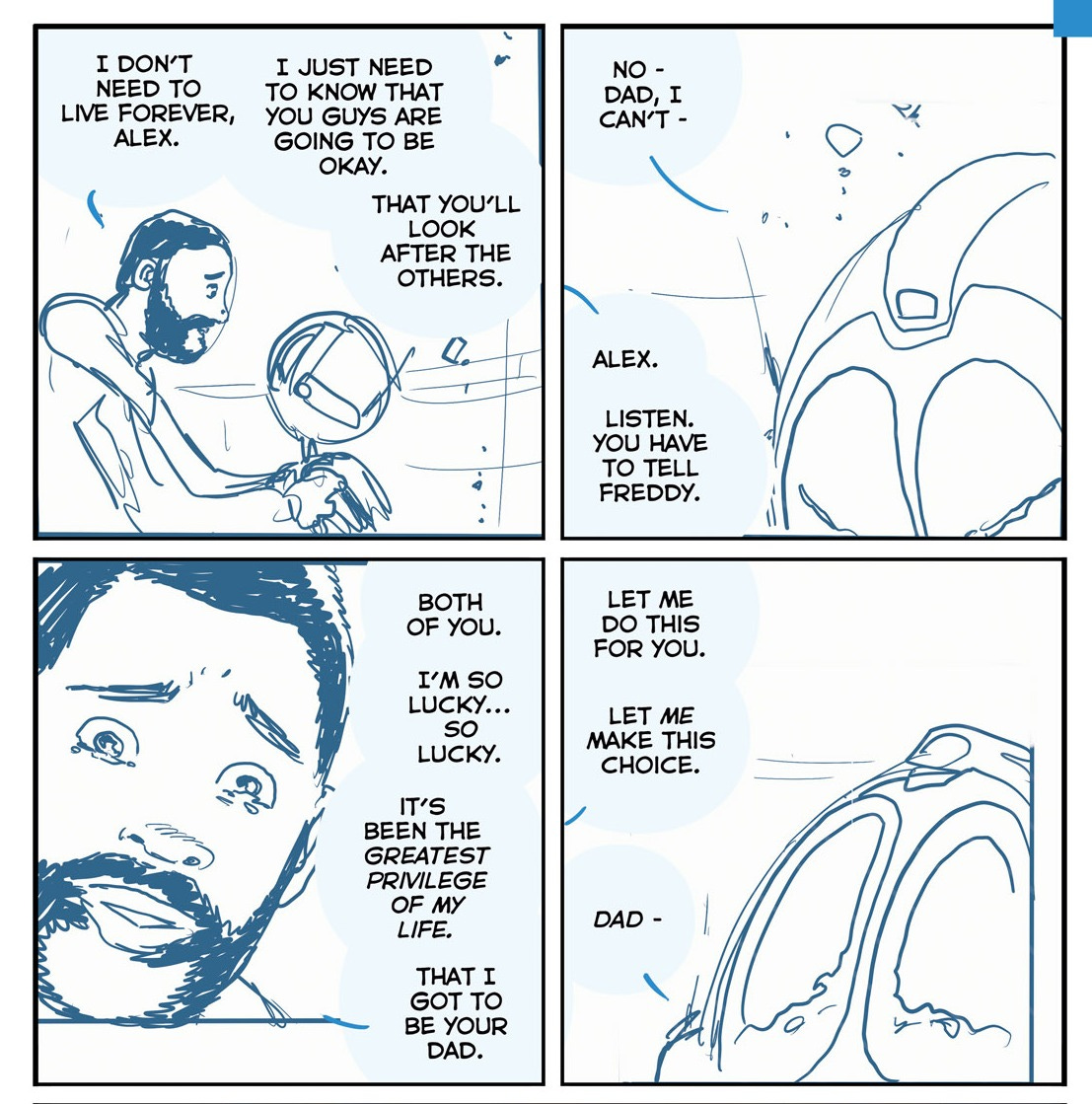

To the extent that this is a coming of age story, I note that Alex is the one who most fully goes through that journey to a kind of self recognition – but Freddy obviously makes a tremendous sacrifice at the climax. So in a way he makes the final protagonist move of the story.

I had a sense of how you were careful to balance out both bros getting their share of story and indeed the fact that Freddy has had the spinoff books. I wondered if you could say something about having two protagonists and, and who gets to travel what distance in terms of character journey.

Neill:

That's a large part of why Freddy got the spinoff books. From a creative point of view, not from any kind of business sense, I could see the back half of the story approaching and I was aware that Alex covers the most story distance in some ways, and there’s all that theory stuff, who goes through permanent and irrevocable change as a character, blah blah blah. The Freddy that exists in my head got really annoyed about it being Alex’s story, and basically demanded his own series of spinoff novels so that he would get more page time!

But also, there’s a stretch in the final comic where Freddy just disappears from the story for a bit. It’s kind of unavoidable, and I was conscious of it, so I just tried to make sure the payoff was worth it. Freddy gets some huge moments in that final section, which hopefully make up for the fact that we’ve gone ten pages with Alex and the baddie talking to one another for a while.

Over the various drafts, there was more and more bulking up of Freddy’s part and Freddy getting his due, being mindful that this is a coming of age story and Alex is the one who comes of age – yet Freddy is co-star, a title character, and lots of people’s favourite! He’s my joint favourite!

When I think of that first image of Alex holding the baby Freddy, that’s sort of the entire relationship in a nutshell. When we first meet them, they’re already at a point where they’re usually fighting and winding each other up, in natural antagonistic brother mode – the default mode for them as characters in this story but perhaps also of all brothers everywhere. Yet underneath the bickering and name calling and constant fighting, driving everyone else crazy, the brotherly relationship is also about love and nurturing and protection, even if we don’t like to admit or talk about it.

Matt:

In terms of protection then, one is protecting someone from threats, from people who wish you harm and wish you ill. Shall we talk about the villains?

The one thing I want to say is that in Robotix, I see the DNA of some of my favourite characters from a series – Pokémon’s Team Rocket! I can’t say I’m that into Pokémon but I will happily watch Jesse and James in action whenever I can.

Where you did you find the villains and did you have to audition villains? Are there ones who didn't make the cut over the eight volumes?

Neill:

With Team Robotix, you’ve nailed the inspiration quite directly!

I guess you’ve got two kinds of villains in MRB. First there are deeply lame people, jerks and losers, who are kind of grubby, like Robotix and the Toymaker. They’re in it for money or self publicity, they’re kind of joke baddies, easy to pile on and make fun of.

Then you have robot baddies who tend to be a bit more ideological or a bit more of a serious threat, who have a serious point of view which we can recognize even if we don’t agree with it.

And then I guess, the final big bad, he’s sort of both, isn’t he? He looks like he’s one type and then turns out to be just another jerk loser underneath. Disappointing as all parents ultimately are!

Matt:

I definitely thought of the villain as being the mirror to Michael as a good dad. There’s a good father and a bad father in this story. What do you, as a father, see of yourself in your ultimate villain?

Neill:

Michael and Roboticus are basically my thesis statement on Good and Bad Dads. It’s pretty explicit in that last volume, they all but say it on panel. And I see myself in both of them to an extent: Michael as the dad I aspire to be, Roboticus as the dad I worry about being.

I’m more eloquent in comics than when I’m talking, but, what I was really asking is, “What are you in this parenting thing for? And do you see this child as a person in their own right who you are lucky to be able to know, whose life you are lucky to be a part of? Or are you treating them as a kind of extension of yourself or some kind of instrument to achieve your goals?”

I think all parents are a bit guilty of that, whatever we do, there’s an element of “My name shall live on beyond me!” We may not like to admit it, but there’s an impulse there, and we might need to acknowledge it and not let it get out of hand…Even if you think you are nurturing your child to be their own person, it’s unavoidable that you impose all kinds of things on your kids - worldview, religion, politics, even just commonplace things like are we a cutlery household or a chopsticks household, a Roses household or a Quality Street household?

Matt:

It makes me think also of the hybrid nature of the book’s ultimate villain, and what you can do when you are thinking through stories with robots rather than humans…What does it do for you to think and tell stories using robots – and how does the nature of the MRB villain play into that?

Neill:

Just at a straightforward physical level, it got a bit tricky! We have a couple of moments edging towards body horror, because suddenly it’s gross and scary – not just fun and games.

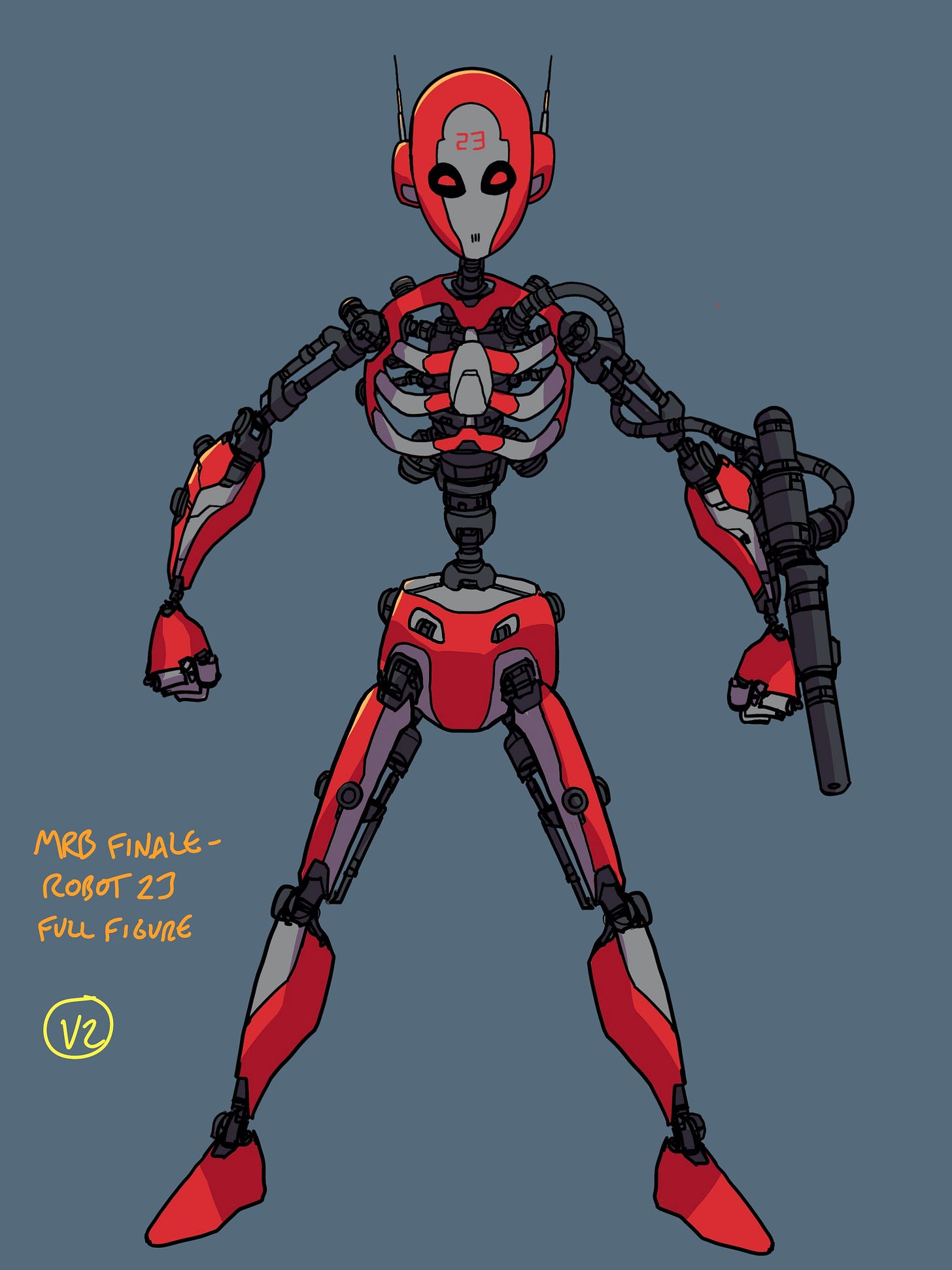

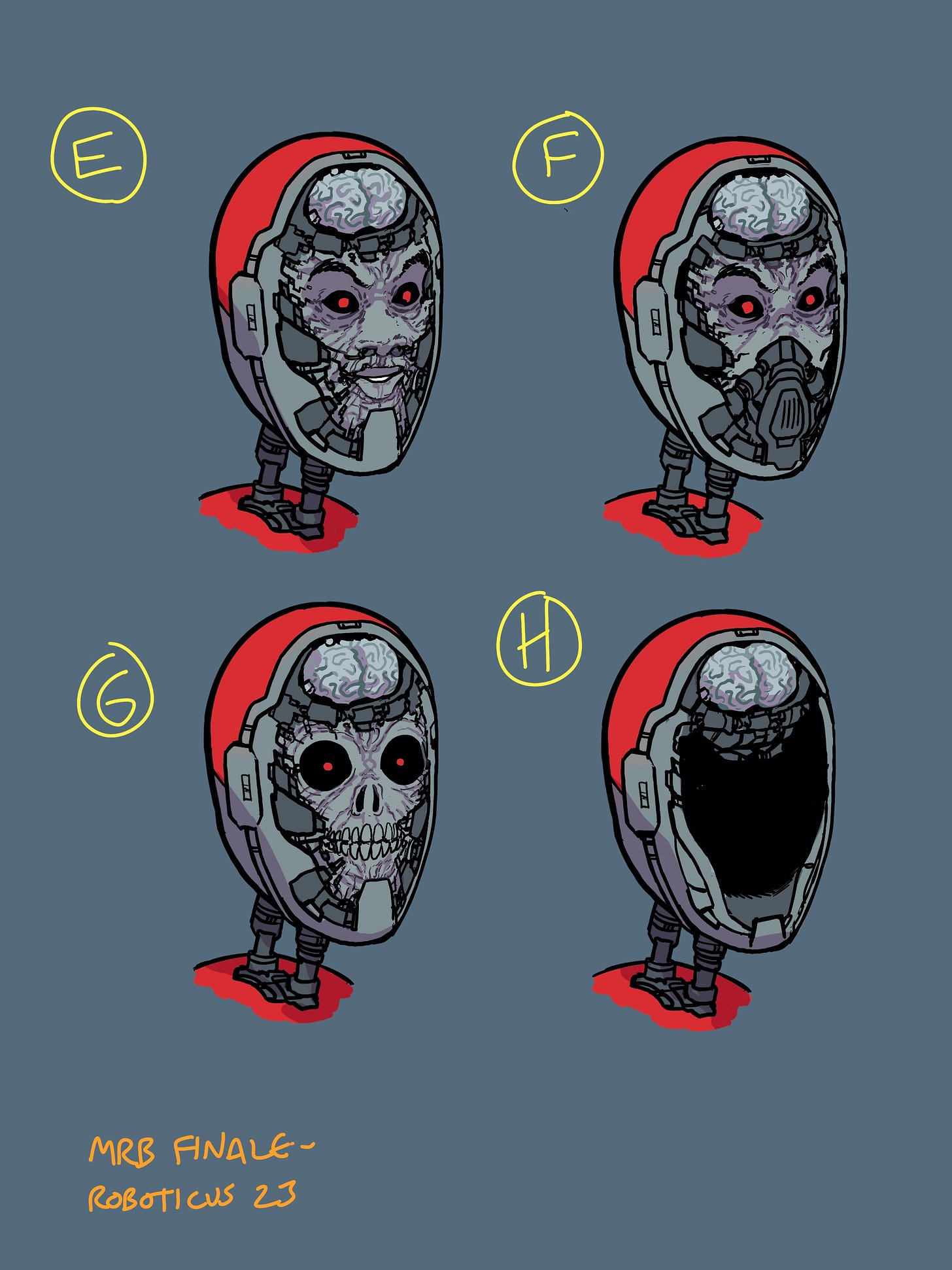

I did eight character designs for Doctor Roboticus when he takes off the mask, ranging from a brain in a jar to a skull and something like Darth Vader. I wanted it to be recognizably him, for it to be his face, because those two pages, that reveal, really have to sell things at a fundamental storytelling level.

So I fought quite hard not for him to be a brain in a jar or a Darth Vaderish half-robot thing. It is pretty messed up looking in its final form, and we did have to think: There are six year olds reading this comic! Are we stepping over a line? Is it too much? How do we scare, but not scar, so to speak?

More generally, that villain character gives you a chance to really get into the big questions of why humans would be making robots. Why are we, as a parent species, creating this child species? What do we hope to gain from this? What are our motives? How should we be treating these children – and how do we hope they will view us? It’s a way of getting into quite big issues of transhumanism, and by the final volume you can address that explicitly instead of dancing around it. So Doctor Roboticus, being one but wanting to be the other, is a fun character to let us get into that.

Matt:

And another dark authorial proxy? Do you also like the idea of being a robot?

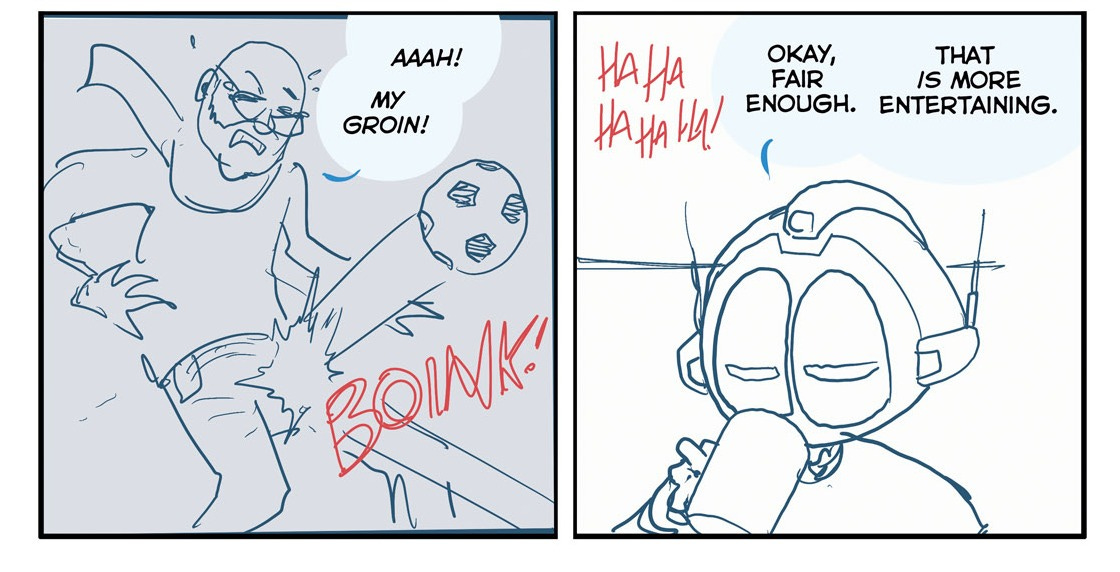

It speaks, in any case, to this way of working you have, which is profoundly philosophical. You’re so self-deprecating when you talk, but actually your exploration of these issues is rather rigorous. You never let it get out of hand in the context of MRB: when Alex gives their moving speech at the UN, the Bros change channel. And they change it to a show where a guy who looks exactly like you, Neill, is hit in the crotch by a ball!. And even Alex says, “Yeah, that’s better than my speech!”

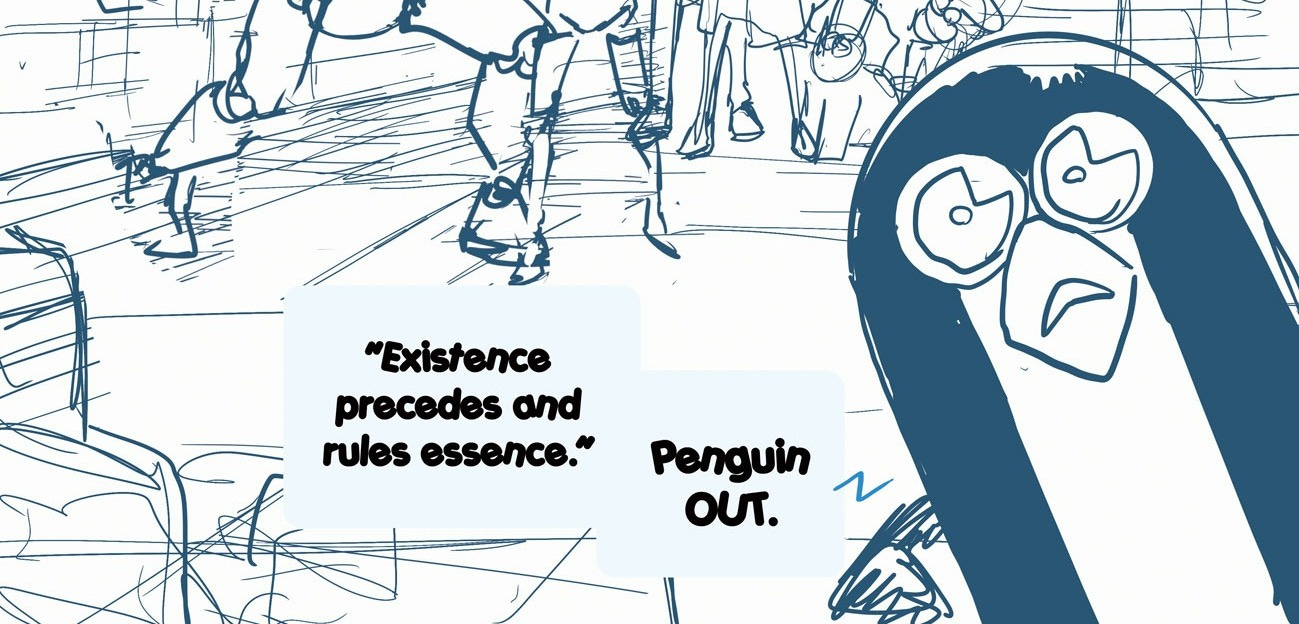

It bring me to the philosophy penguin, another character and another facet we haven’t gotten to yet. I wondered how he comes into the story, why his quotes all comes from existentialism, and what he has to say about robots and their agency?

Neill:

Again, he was a happy discovery along the way. I knew early on that I wanted some weird kind of chorus. You have the main action going on and then while your protagonists do all their protagonising, you’ve got a bunch of little weirdos hanging around the edges, watching the fight or whatever. I don’t think I thought it through to any greater extent than wanting some cool little weirdos to serve as a Greek chorus, but commenting on the action in really non-sequitur ways. So you have a French-speaking gorilla and the triceratops who just barks and the penguin who exclusively speaks in quotes from Sartre. It’s the one use I’ve ever found for my philosophy education!

I don’t claim to be an expert in any way, or to have really made through any more than a few pages of Being and Nothingness, which is, to be fair, brutal. I like Sartre’s fiction more than his philosophy, at least to read for pleasure. Yet, even though the philosophy feels really hard going to me, I also find it in some way funny.

Experience has borne me out on this. You pick a couple of choice lines from Being and Nothingness and put them in the mouth of a robot penguin? Kids find that hilarious! They sound so comically bleak, bleak in striking ways, and yet the penguin ends up not just being a joke character, there to make kids laugh and make me laugh; he becomes the moral heart of the thing. There was such joy in the final volume where he becomes the mechanism for how their powers are restored and the Bros are reborn. They come into their power again through hearing one of his weird little Sartrean lines – and it’s kind of the thesis of the story, that freedom is what you do with what’s been done to you.

I think this is every human being’s life story. You didn’t ask for all this, you were forced into this world, you were not consulted on the matter! Whatever part of the world you find yourself in. Whatever form that takes, whoever you are. Whatever expectations you find put upon you because of where you’ve been put in this world. What’s yours – what’s you – is what you do with it.

Matt:

That makes me wonder about the characters you chose to put in this world. Thinking about the visuals as much as anything now…where do you find your human characters’ faces? How do you figure out what someone’s going to look like in your comic?

Neill:

A lot of the human characters have been there since page one, and tended to be locked in from very early on. Maybe I could’ve taken more time to work from reference, or not just use my default way of drawing people, but the truth is I found them all on the page as I drew them. Sometimes that took a few hundred pages or so, which is unfortunate! Maybe there I would’ve benefited from more lead time, to really find the faces before I started.

The truth is, they’re just sort of there. Before you start drawing you go through a casting process in your head: Who would this person be? Who do I want them to look like? None of the characters I based on a particular real person, but there’s a sense there of how they ought to look.

Matt:

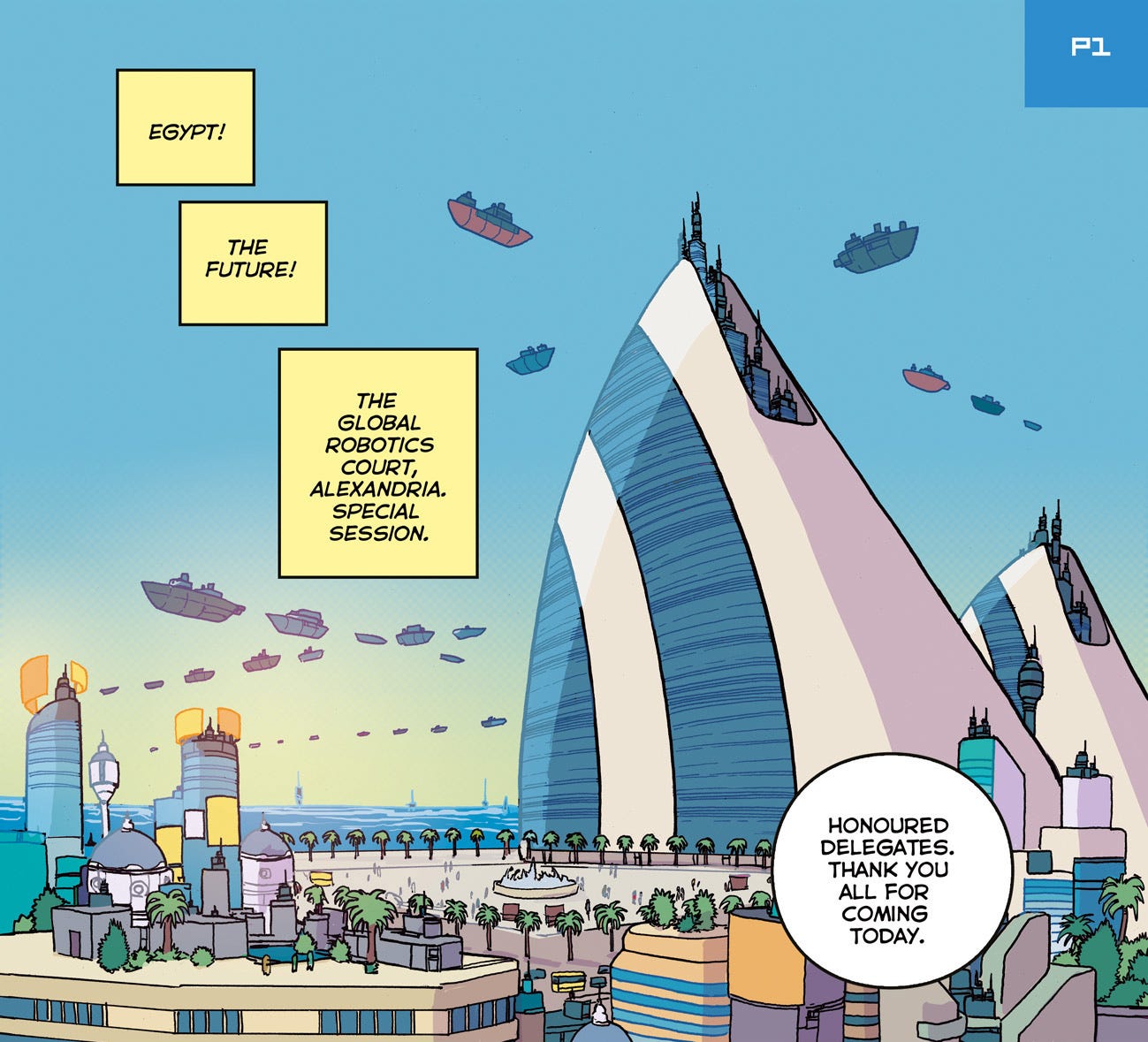

Thinking back to the supporting cast, and the French speaking gorilla, has me wondering about national identity in MRB. At the start there’s some ambiguity about whether RAID is a British or international agency; it’s very evidently a global authority by the end of the series. And there is a global robotics court also. But the UK still has a monarchy – even if the Bros’ mother takes a little jab at them! – you have robot soldiers with busbies and so on. Between Sartre and the gorilla, there’s a lot of Frenchness in this book, but there’s also something about this being a very British comic book which is still open to the world, in dialogue with the world. What’s going on for you when you think about nations and identities in Mega Robo Bros?

Neill:

This is a comic for kids which is half sitcom, half action movie; you don’t have to get too into the nuts and bolts of worldbuilding, like how does global governance work and so on? And yet, you set a scene somewhere and that does have implications, even if you don’t dwell on them.

The key thing is that it’s a story for children set in the future. And for all that you get into some challenging or slightly scary places, you are still imagining a future in which the world still exists and it’s basically okay. Perhaps it’s not some shiny utopia, it’s just that everything seems to be just about working…Then again, even that level of optimism might seem boldly utopian right now.

The point is to give kids permission to think about the future as a place of hope, not just dread. I grew up in the era where we were all convinced we’d be wiped out by nuclear weapons, and that did shape my personality.

Matt:

Completely. I remember the black AIDS monolith from the old, terrifying British public health ads on television blurring in my mind with the black silhouettes of the nuclear weapons and submarines and bombers from Raymond Briggs’ When the Wind Blows. Pure horror.

Neill:

Kids today are growing up being told that the world is burning, that we are destroying our own future; we have people dealing with climate grief and the emotional ramifications of huge, catastrophic global change; it’s so dark, and yet without any false sugarcoating we have to also offer that sense that the future will exist and you should feel free to live your life with that expectation, not just with the apocalyptic alternatives that might in fact be too horrific to contemplate.

So the worldbuilding of MRB is basically saying, what would the institutions of this still-existing world be? There’s a certain level of international cooperation, some kind of evidence-based respect for science, a drive to find solutions through international collaboration; all of this is implied by the fact that London exists and isn’t just underwater, never mind the global robotics court and all the rest of it! We must have gotten our act together as humanity to some extent, just for this story to even be happening, you know?

Matt:

Of all the unexpected things, I find myself thinking of the existential psychotherapist Irvin Yalom, his idea that to be human is to go on despite awareness of the reality of death.

Neill:

I think that’s a very good description of the human condition, ultimately. We go about our days, make tea, try to do our jobs and be good people and have a nice time while being aware that nothingness is coming down the road towards us permanently and irrevocably, and at whatever point it chooses.

Alex and Freddy seem pretty well constructed, sort of functionally immortal as long as they maintain a basic level of upkeep and avoid things like flying into the sun or whatever –Doctor Roboticus in the final volume kind of implies that in theory they could live forever…and yet, though they often feel quite invulnerable during the earlier books’ fight scenes when they’re punching a bunch of robots’ heads off, by the final books they are confronted with the end of life. It suddenly feels very different. They face death and the concept of death in a way not all children have to.

And when we face death for the first time, we might even find it funny, because it’s so peculiar. Funny and weird! And as we get older, maturing, recognizing the reality of it, and that it applies to you, well, part of growing up is perhaps finding that it’s less funny. That this is something that also applies to you, and you must reckon with it.

Because of the nature of Alex and Freddy, in some ways they have a free pass in terms of not having to deal with it – and yet, by the end, they both do in their own ways and that is a very humanizing thing. Perhaps the ultimate humanizing thing.

Matt:

Mmhm. Like in Asimov’s Bicentennial Man, that’s what finally makes the robot human in the eyes of the world, he accepts mortality.

But also I think Alex and Freddy both make irrevocable choices, which are therefore adult choices. And then because this is an adventure comic about robots, they are rewarded for this sign of maturity, the ability to make such a consequential choice and take responsibility for it.

Let’s just have a quick little palate cleansing question here: where does “Kerchatov” come from?

Neill:

Oh my! That’s from my very brief attempts to do any kind of scientific research on fusion and how plasma works. So many kids have talked to me and been shocked to discover that it’s not a thing – it’s not a real thing. I made it up entirely! But if you say it with confidence and in the context of a story, people just go along with it.

However, at the outset, when I was briefly trying to learn anything about physics at all, I came across some scientist with that surname who had done some work in the field of plasma and I just went, “That’ a cool name”. And it just had the right ring for my story. Not a character but some background figure in the world of this story. It just makes things sound legit in a weird way, that somehow this name has the exact right ring to it, which confers legitimacy.

Matt:

It’s just the right level of light-touch worldbuilding: knowing when to have a specific name, when to just say, “You don't need to know how this thing works.” II think you nailed the sweet spot of that.

So I thought to bring us to a conclusion that not just a dismal existential wallow…

Neill:

Death and inevitability!

Matt:

The flip side of being and nothingness is nothingness and being.

There was a moment before the Mega Robo Bros existed when there was nothing.

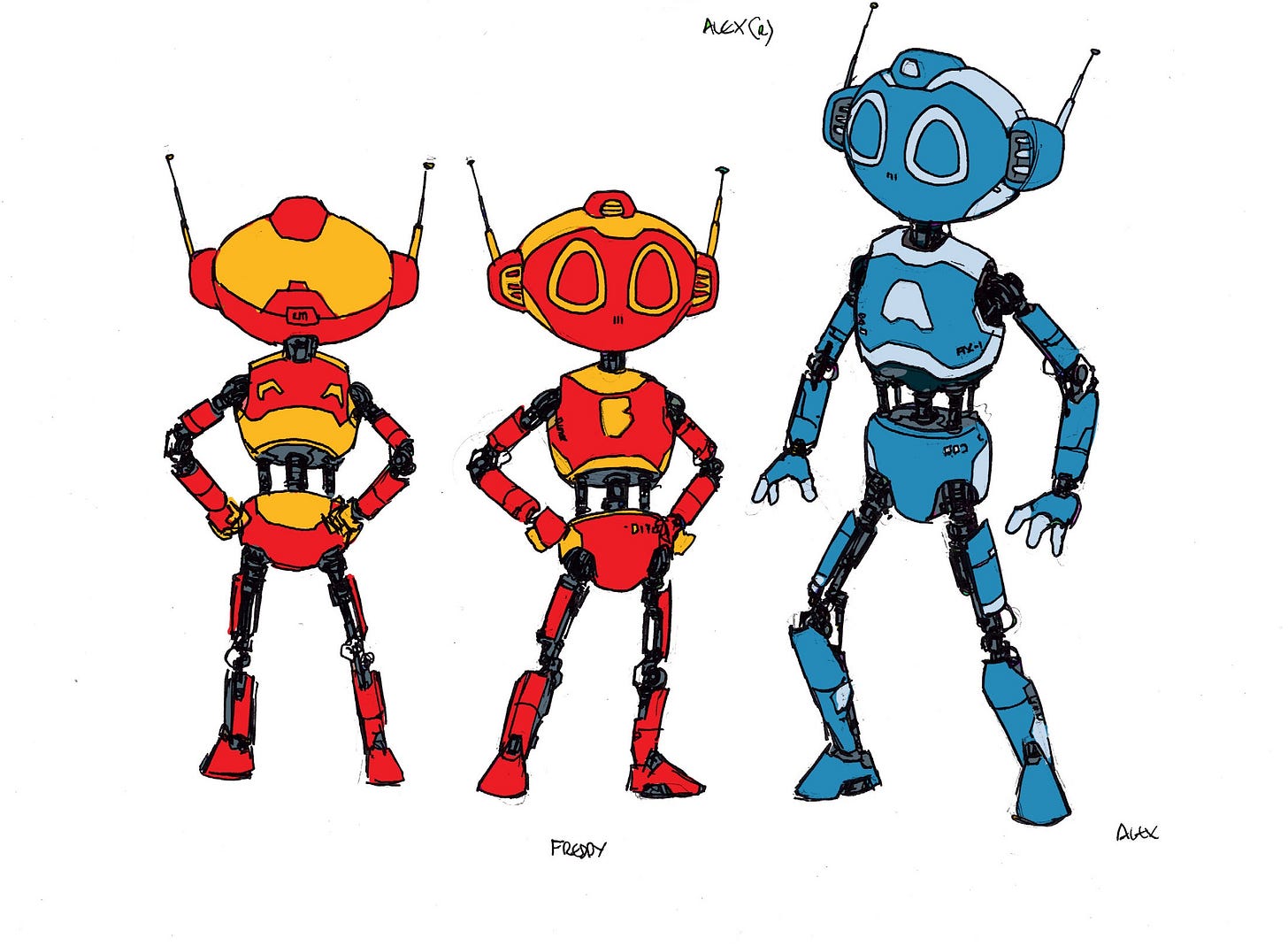

And we've spoken before about, okay, there are two brothers who happen to be robots. You had all these ideas for how that would work: Maybe they're little dudes who fit in school backpacks, like Transformers type things. Maybe they're humans that didn't know they were robots, but then you saw: actually that's going to be a pain in the pages of the Phoenix, it’ll lead into body horror.

And then you said the look was the starting point. Once you had robots in school uniforms, you knew there were schools, so you knew, the world is like ours in many ways, despite its futuristic tinge.

But do you remember the moment when you first drew the Bros and thought, “Yeah, that's them.”

What was that moment like and how did you feel when you first saw them?

Neill:

They did indeed go through a lot of version, and the concept of the strip was also evolving as I went through all of those versions: How robot-y are they going to look? How human or inhuman? Are they going to be cool chunky little Gundam guys? That wouldn’t look right in a school uniform! I can’t give them shoulder pads and rocket launches and vents and stuff…Now they just look like artist’s mannequins.

So I went through all these different versions, and I did one that was inspired by some little commercially available robot that had big round eyes, was made to be cute, and I drew something in that vein, but in a school uniform. Big round blank friendly eyes. And then I thought: if you actually had a range of emotions playing across that, it could be really fun and interesting. Then you have a character.

I think I had Freddy first, wearing his school jumper and his backpack, and just sort of looking up at someone as if he were holding their hand at the school gate. And that was the moment that it became: “Oh, yeah, this is a character now. This is a story now.”

So Freddy came first, I guess.

Matt:

And I guess those earlier versions you tried did get their moment because we see earlier versions of the robots within the world of MRB. Like Wolfram’s look is in dialogue with Mazinger Z toys, and Wolfram does have those big cool shoulder pads and so on.

Neill:

Absolutely. Those earlier drawings did completely inform the design of characters like Wolfram. A big, dark, shiny, more robot-y looking elder brother who comes from that early “Let’s learn to draw some robots!” phase of the process.

Matt:

Mega Robo Bros reminds me in some ways of the 2005 Doctor Who relaunch in that both series seemed to arrive almost fully formed. They come out of the gate swinging and already feeling close to the platonic form of the story.

But are there any places now where, in hindsight, you think: “Oh, I fumbled this a bit, or I’d do it differently now, or this bit didn’t play out, or ended up a bit extraneous”? As a reader, it’s hard to see anything like that. It looks smooth and intentional. But maybe there are a few odd bits, like the kibble on a Transformers toy, that remained in the story but never got used?

Neill:

Well, particularly with the very early stuff, there were lots of strips and little stories that appeared in the Phoenix but that, as we came to shape it into book form, didn’t quite fit, or there just wasn’t room for, and so fell by the wayside. So I guess those are the kibble. And there’s a few little bits there that I’m sorry have been lost to the mists of time and the Phoenix back-issue mountain, but… nothing essential, really.

At the risk of sounding pleased with myself about something I’ve ever done, which is not my usual style - it all worked out. I’d chalk a lot of that up to good editing, and the pressure of space – there simply wasn’t room for things that weren’t there for a reason. I had a very clear sense of the ending, and I stuck to that, I knew what I was aiming at ultimately, and therefore I only put in things that were relevant to reaching that point. I think pretty much everything goes somewhere. There aren’t many dead ends.

Matt:

Once a story goes into the world, it’s no longer within your responsibility or within your gift to say how the world receives the Bros and what difference that story makes in the wider world. But still, in terms of who you are and how you feel about the Bros and their story…if you look back at the Neill of ten years ago and where you are today, what difference has it made to you spending time with Alex and Freddy, being in their world and telling their story?

Neill:

Well, it’s been a funny old ten years for us all, to say the least. There were many points where I was enormously grateful to spend a lot of time in my imagined future version of the world, rather than the world which was unfolding around me. Like, 2016 felt like a big setback for the cause of evidence-based international cooperation around the world. And we’ve been dealing with the ramifications of that in many ways, in many parts of the world, since then.

So I was able to take my bad feelings about the ways things are and spend time in a world where maybe some of these changes were reversed, some of the trends were turned around, and the arc would still point towards a better world. That was good – and not just for my sanity!

It’s also about presenting kids with a future where, even if things look bad now, it’s not inevitable how they will play out. I found that psychologically useful personally, but also potentially a gift to readers – both kids and perhaps the parents who were reading along!

But the other big thing that is very intrinsically and intimately and unavoidably tied to the journey has been raising a kid for ten years. You know, he started as almost a little Freddy and now he’s coming of age, he’s at Alex’s point in life.

We’ve all been on that journey together as a family and it has fed back into the story and you can’t pull it apart. It’s weird and I’m very grateful to tell a story that is both about growing up and also about parenting. That latter part isn’t really a selling point for kids, but I can see the story is also about that nonetheless. Having that opportunity to see work and life tied together, organically and in a way where the narrative arc matches on and off the page, finishing the story as my son finishes his GCSEs and is technically grown up…that is a unique thing that I do not expect to ever experience again in life. It was wild and intense and kind of amazing. No storytelling, no story making experience will ever quite be like that again.